[ad_1]

ET BrandEquity.com brings the thirty-second part of the weekly series of Strategygrams.

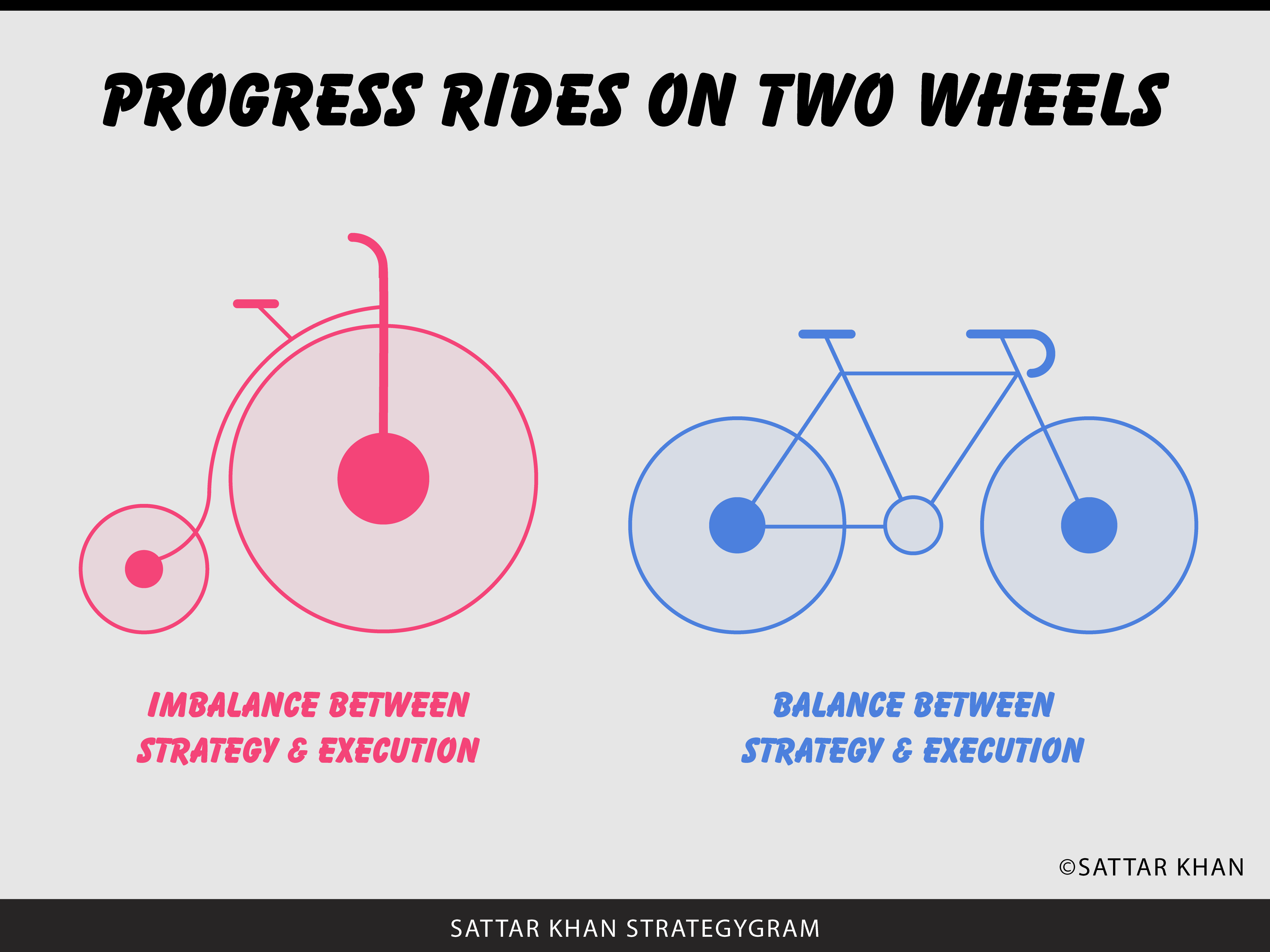

This week’s Strategygram titled ‘Progress Rides on Two Wheels’ is part of the series created by Sattar Khan, a brand strategy consultant. Each Strategygram condenses one strategic thought into one image. The collectible series is a visual guide to strategic thinking and provides handy image prompts for your brand strategy workouts.

Admit it, you’ve heard people arguing over which is more important: strategy or execution.

Somebody remarks: “It was a brilliant strategy but it was messed up because the company couldn’t execute it properly.” Really? If it were such a brilliant strategy, why didn’t the strategy take into account the company’s capability and culture?

Somebody else states: “The execution was flawless but the strategy was flawed.” Huh? What was the point of bothering to do the wrong thing perfectly?

Strategy minus execution is fruitless brainwork. Execution minus strategy is aimless busywork.

Strategy and execution are like two wheels of a bicycle—having just one of them gets you nowhere. If you don’t have both in balance, you can’t make progress.

Strategy decides what to hunt, where, and why. Execution decides how to take the target down.

What’s more, you can’t decide on the what, where, and why without the how, when, and what if.

Strategy and execution are inter-twined because the company is undertaking a calculated foray into an uncertain, shifting future, and that too against the headwind of competitive forces.

Only dead things react; live things interact—which is to say that competitive forces have a nasty tendency to hit back. As they say, “No battle plan survives contact with the enemy.”

(That thought was reportedly first expressed in 1871 by Prussian Field Marshal Helmuth von Moltke who said:

“No plan of operations extends with any certainty beyond the first encounter with the main enemy forces.

Only the layman believes that in the course of a campaign he sees the consistent implementation of an original thought that has been considered in advance in every detail and retained to the end.”

Or, if you prefer a more recent version of that thought, here is Mike Tyson, then the reigning heavyweight boxing champion of the world—the first heavyweight boxer to hold the WBA, WBC, and IBF titles simultaneously, “the baddest man on the planet”—replying to a question during an August 1987 press conference about his loudmouth opponent, the Olympic gold medallist Tyrell Briggs, who had never lost a fight since turning pro, who had a formidable advantage over the shorter Tyson in height (6 feet 5 inches versus 5 feet 10 inches) and reach (80 inches versus 71 inches), who had been bragging about his plan to trash Tyson during their upcoming fight in Atlantic City, New Jersey, in October 1987.

‘Iron’ Mike’s response? “Everybody has plans until they get hit for the first time.”

Postscript: Tyson won by a TKO in the seventh round of a scheduled fifteen-rounds fight. So much for plans hitting reality.)

Instead of thinking in terms of a binary divide—strategy versus execution—it’s better for organisations to think in terms of bigger and smaller choices made in complex and fluid circumstances.

Strategy makes the macro choices and execution makes the micro choices.

The big choices of strategy are embedded in the smaller-scope choices of individual action or the implementation of individual components of the strategy.

In a sense, this is like brand synecdoche, where a part epitomises the whole.

It used to be said about that famous carbonated cola soft drink brand available in contoured glass bottles that a person who saw a shard of a shattered bottle would immediately recognise the piece had come from that cola brand’s bottle.

That is what proper execution is like: the small part represents the big picture, micro actions embody the macro ambition.

Perhaps we should stop using terms such as ‘execution’ and ‘implementation’ because those terms unwittingly underplay the importance of making good things happen in moments of encounter with reality.

The one-way path from idea to implementation is something we learn about in textbooks, not from life. The interplay between strategy and execution (if we are to use that term), requires a two-way flow of information between the frontlines and the headquarters, so that an organisation can adjust and adapt its strategy for success in emerging and becoming-clearer conditions.

The disastrous alternative—where a headquarters team adopts the view that unpleasant-news-is-a-sign-of-your-incompetence and frontline personnel are willing to falsify reports for their blinkered and dogmatic bosses—was most vividly dramatised during the Vietnam War.

On the one hand you had headquarters staff whose mindset was epitomised by this statement of the country’s famous National Security Advisor, who later became the Secretary of State, in his remarks to NSC aides in July 1969:

“I refuse to believe that a little fourth-rate power like North Vietnam doesn’t have a breaking point.”

And, on the other hand, you had a meretricious—attractive but having no real value—key performance indicator: body count. “That was the deal, body count,” said a subsequent Secretary of Defense. “You used that body count, commanding officers did, as the metric and measurement as how successful you were.”

Because the key performance indicator didn’t make sense with ground realities, falsified reports were sent up the chain of command to appease cocooned headquarters staff. As a Pulitzer Prize-winning writer summed it up: “The politicians lied. The generals lied. Both lied to keep their jobs, not for any nobler reason. Others lied to make a bloodstained buck.”

Truth can be unpalatable, but it can break the back of your strategy. How can a strategy guide everyday actions sensibly?

Think about the case of major airlines who, under pressure from low-cost regional airlines, decided to launch their own low-cost carriers (often, unfortunately, with the baggage of cost overheads, profitability requirements, and a ‘proper airline’ mindset).

In contrast, consider the mindset of a co-founder and chief executive of one of the most profitable regional airlines, an executive who, when large airlines were struggling with near bankruptcy, continued to run one of the most profitable airlines for decades and was repeatedly voted as the best CEO in the airline industry, with Fortune magazine going so far as to call him “perhaps the best CEO in America.”

This is what happened during a meeting with a visiting business magazine journalist:

“I can teach you the secret to running this airline in thirty seconds,” said the chief executive.

“This is it: We are THE low-cost airline.

Once you understand that fact, you can make any decision about this company’s future as well as I can.

Here’s an example. Tracy from marketing comes into your office. She says her surveys indicate that the passengers might enjoy a light entrée on the Houston to Las Vegas flight. All we offer is peanuts, and she thinks a nice chicken Caesar salad would be popular.

What do you say?”

The journalist stammered for a moment, so the chief executive continued:

“You say, ‘Tracy, will adding that chicken Caesar salad make us THE low-fare airline from Houston to Las Vegas? Because if it doesn’t help us become the unchallenged low-fare airline, we’re not serving any damn chicken salad.’”

That’s macro strategy meeting micro decision-making at the everyday level.

You can infuse people with a sense of mission. You can re-engineer processes to facilitate, monitor, and reward progress. You can shape the organisation’s culture to galvanise collaboration across departments and units (which is far more difficult to accomplish than top-down alignment).

But in the end, all that work with people and processes, culture and communication, ratings and rewards, will come down to the decision-making clarity epitomised by a single everyday question such as: “Will adding that chicken salad help us become THE low-fare airline between Houston and Las Vegas?”

What’s your question?

Check the first thirty-one Strategygrams: ‘Speed Kills’, ‘Half Bridges Don’t Work’, ‘No Contest’, ‘The Silent Clue’, ‘Who’s For Lunch?’, ‘Competition Is A Monster’, ‘The Distinctive Sells The Difference’, ‘Strategy As Story’, ‘Timing Beats Speed’, ‘Conquering Fort Customer’, ‘How Are You Different?’, ‘The Villain and The Hero Inside’, ‘Galileo’s Discovery’, ‘The Strategic Logic Chain’, ‘The Brand Experience Trio’, ‘Deer in the Headlights’, ‘Do the math’, ‘An insight is like a tram car’, ‘The leap of insights and ideas’, ‘The Three Monkeys of Strategy’, ‘The Breakthrough is in the Question’, The tango of problem solving, ‘Getting to Simplicity’, ‘Head on a Platter’, ‘The Slippery Slope of Good Enough’, ‘It’s Renew or New’, ‘The Elasticity of Affection’, ‘Aesthetic Seduction’, ‘See Different to Think Different’, ‘Mirror, Mirror on the Wall’ and ‘Strategygram: Winning gestures’.

-Sattar Khan can be reached at sattar1000@gmail.com.

[ad_2]

Source_ link